Pointers for Practice: How to Apply the Safeguarding Process to Practice

Whether identifying concerns or making assessments to establish care, support and safety needs, practitioners should follow a similar process. However, the task will vary. For example, the aims and objectives will be different for a practitioner in a family centre who is identifying concerns, to the aims and objectives of a multidisciplinary assessment and intervention to safeguard a child at risk.

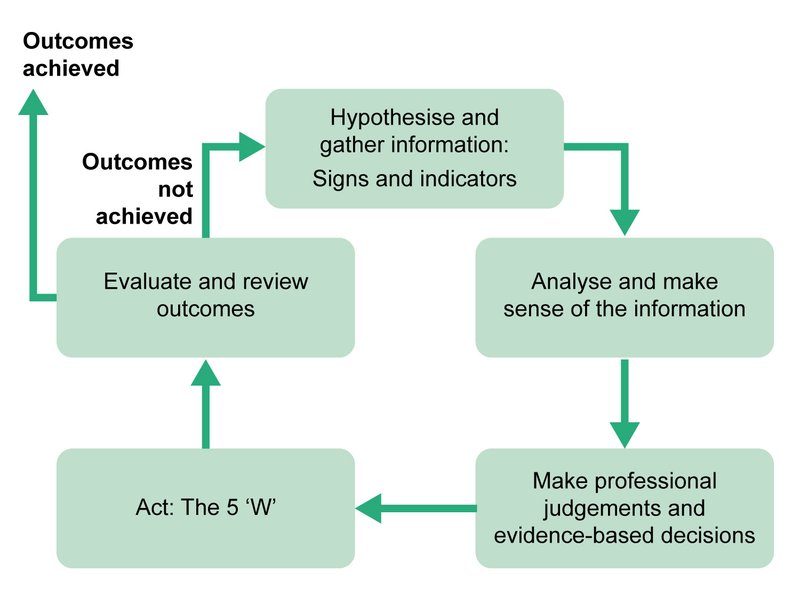

The over-arching process is shown in Table 3. Each stage is considered in general terms below.

Hypothesising and Gathering Information

Consciously or unconsciously, whether reporting abuse or initiating enquiries in response to a report, practitioners begin by hypothesising or theorising as to whether the child or adult is at risk of harm. What is causing me to think the individual is at risk of harm? And to confirm or refute the hypothesis practitioners need to obtain information. Information-gathering begins by considering: what do I know?

- Information-gathering should focus on the signs and indicators of possible abuse and or neglect. For example, for those considering reporting a case of a child or adult at risk it means obtaining sufficient information to decide whether to make a report to social services. For practitioners responding to a report, the purpose of information-gathering is to gain insight into the world of the child to understand whether they need safeguarding and/or have care and support needs.

- The role and responsibilities of the worker will affect the information they have at their disposal.

- Information gathered should be ‘proportionate’. It should be sufficient to inform decision-making. For example, when making initial enquiries about a child who has been subject to long-term neglect family history could be significant.

- When gathering information, detail and evidence of concerns about harm should be obtained. For example, ‘the child is inappropriately dressed for school’ means little. ‘The child arrived at school in sandals with holes in the soles. She had a thin cardigan, a cotton dress, no underwear and no coat even though it was February’ is much more specific. If the information gathered is hearsay or professional opinion this should be made clear.

- The service-user and their carers should have opportunities to provide information about their situation, their wishes and feelings. Communication approaches that promote engagement and information-sharing should be used. For example, asking what language they wish to use; drawing on interpreters and advocates.

- Information gathering and sharing should be in accordance with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulations.

- It should be transparent to the service user and undertaken with the consent of parent of the child at risk. However, information can be shared without consent if to do so would place the individual or others at increased risk of harm.

- Information gathering should not focus merely on gathering evidence to confirm one’s hypothesis. It is important to gather information about both the positive and negative aspects of the situation.

- Record information gathered.

Making sense of the information

Having gathered the information, the next stage in the process is deciding what does this information tell me about the child I consider at risk of harm? Does it confirm or refute the hypothesis? Do I need to test further, consult and/or consider alternative hypothesises?

At this stage, irrespective of the reason for the assessment, there are questions that the practitioner should ask of themselves:

- Do I have enough information to analyse and make a professional judgement? If not, what more do I need? How will I obtain it?

- Have I seen and spoken to the individual? Have I listened to what they have to say and taken their wishes, views and feelings seriously?

- Do I have a clear understanding of the personal outcomes the child, family or adult at risk wish to achieve?

- What weight can I give to the information gathered? For example. is the information evidence-based, hearsay or professional opinion?

- Do I need to revise my hypotheses in view of the information obtained and analysed?

- Do I need professional advice and guidance? Who can I contact? (see section on obtaining advice)

Diagram 1 the identification, assessment, planning, intervention and review process

Decision-making and planning

At this point in the process practitioners should be asking: _w_hat do I need to do, taking into account my role and responsibilities to protect, care and support the child? Are immediate actions necessary?

In the same way that the information gathered should be proportionate so should the response.

The following questions should be considered:

- What does the information gathered tell me about risk of harm and protective factors?

- Do I have enough information to make an informed decision about next steps or should I gather more? If so, what do I need to know? Who should I consult?

- What are the wishes of the child at risk, their parents?

- What is required of both family and practitioners to protect the child from harm when possible without breaching the right to family life? If there are several options, consider the advantages and disadvantages of each. For example, lengthy waiting lists, location, appropriateness of available services.

Action/ Intervention

Actions should be designed to ensure the child is no longer at risk of harm and their care and support needs are being met. Practitioners should be asking themselves: how will the identified actions - immediate and longer-term - contribute to keeping the child safe and improving their lived experience?

At this stage the 5 ‘Ws’ should be considered (the application to different responses to risk of harm are considered in the relevant sections). Practitioners and the adult or the child at risk and their family and carers must reach a shared understanding of the following:

- Why interventions are taking place and how they are designed to achieve identified person-centred outcomes

- What interventions will be undertaken to achieve the desired outcomes and the rationale for these interventions. For example, why the parent should attend a parenting programme

- Who is expected to do what? This is essential so that both practitioners and the family understand exactly what is expected of them as part of the intervention and how these actions should achieve the desired outcomes.

- When this will happen. It is useful to agree timescales with measures of progress.

- Where interventions will take place.

Evaluation

- Evaluation and review are necessary to see if outcomes have been achieved. If the agreed outcomes have been achieved, then the case may be closed. If however, the outcomes Does the child and their family or the adult at risk believe the quality of their lives and their well-being has improved?

- What evidence do we have from the service user and practitioners that the agreed outcomes have been achieved?

- What interventions worked?

- What actions did not contribute to improved outcomes?

- Do we need to revise interventions for this individual?

What have not been achieved, then the process will need to be revised or start again.

Have the agreed person-centred outcomes been achieved? What evidence do we have? If the outcomes have not been achieved what should happen?

These questions are important to ensure presumptions are not made that the risk of harm has reduced without evidence to support this. Practitioners should consider the following:

- Information do we need to assist us make this decision?

- If the outcomes have been achieved should the case by closed? Are other sources of support required to maintain current levels of safety and well-being?

- Does the child at risk their family or the adult at risk and practitioners share a common understanding of the review conclusions and any additional assessments etc that will be completed because of the evaluation?